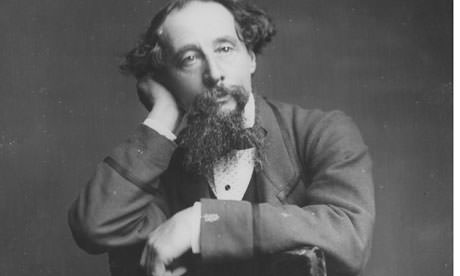

G.K. Chesterton called him “the last of the great men”.[1] It was not only that Charles Dickens, the subject of Chesterton’s essay, was a great man because he saw a great need, that he obviously felt a great burden, and followed a great vision to lift that burden by focusing his enormous literary gifts on relief for the poor, working-class children suffering in the bondage of his industrial age; it was that he saw beneath the soot-stained faces of the children, seemingly incapable of smiling. Dickens could see them laughing. He saw them as people. He saw them, and he depicted them in his now-classic novels, in the fullness of their humanity. Dickens, unlike many well-meaning liberal activists of his own day (and ours), knew that the poor would always be with us,[2] and that they had a nobility and a humanity that was quite undiminished by their lot in life. The poor are good. They are bad. They laugh. They dance. They giggle at the sight of kittens playing with the yarn made in their industrial nightmare, and they cry when they are hungry. They marry and give in marriage. They have families. They have honor unto themselves. In other words their poverty did not hinder their living. Now, to be sure, Dickens saw that the inhumanity of a new Industrial Age without compassion or justice made living difficult for the least of his fellow-man. This great gentleman saw what became a burden for him and others— that the little children should not be yoked to the cogs and their childhood deprived by the wheels of an uncaring industry. So he wrote. He advocated. He spoke. And, as in the days when John Wesley preached for the rights of the poor, or William Wilberforce argued against the injustices of slavery, Dickens helped to bring about reform in child labor laws in the Industrial Age. And children were set free. Neil Postman’s indictment of our age, in his Disappearance of Childhood,[3] was recognized by people in Dickens’ age. Things changed for the better.

G.K. Chesterton called him “the last of the great men”.[1] It was not only that Charles Dickens, the subject of Chesterton’s essay, was a great man because he saw a great need, that he obviously felt a great burden, and followed a great vision to lift that burden by focusing his enormous literary gifts on relief for the poor, working-class children suffering in the bondage of his industrial age; it was that he saw beneath the soot-stained faces of the children, seemingly incapable of smiling. Dickens could see them laughing. He saw them as people. He saw them, and he depicted them in his now-classic novels, in the fullness of their humanity. Dickens, unlike many well-meaning liberal activists of his own day (and ours), knew that the poor would always be with us,[2] and that they had a nobility and a humanity that was quite undiminished by their lot in life. The poor are good. They are bad. They laugh. They dance. They giggle at the sight of kittens playing with the yarn made in their industrial nightmare, and they cry when they are hungry. They marry and give in marriage. They have families. They have honor unto themselves. In other words their poverty did not hinder their living. Now, to be sure, Dickens saw that the inhumanity of a new Industrial Age without compassion or justice made living difficult for the least of his fellow-man. This great gentleman saw what became a burden for him and others— that the little children should not be yoked to the cogs and their childhood deprived by the wheels of an uncaring industry. So he wrote. He advocated. He spoke. And, as in the days when John Wesley preached for the rights of the poor, or William Wilberforce argued against the injustices of slavery, Dickens helped to bring about reform in child labor laws in the Industrial Age. And children were set free. Neil Postman’s indictment of our age, in his Disappearance of Childhood,[3] was recognized by people in Dickens’ age. Things changed for the better.

This morning I thought of Chesterton’s essay, and of Charles Dickens, and of these things, as I went into a Dunkin’ Donuts near my home. I was bringing my son to an early morning training meeting for Sunday school. As a senior high student, my son was chosen, happily, to instruct and mentor younger boys in the faith. He teaches Sunday school each Lord’s Day to sixth grade boys. I went in to get his normal early morning treat, an old-fashioned doughnut (as well as a munchkin for our Welsh Corgi that always waits in the back seat for her treat). While standing in line my eyes gazed on the spectacle that struck me as horrible and decrepit as any 19th century textile mill or steel factory employing—abusing—little children. There, before me, at the orange tables, were parents and their newspapers and iPads and emails, and, at every table (a veritable assembly line) were their children—playing on their iPhone, still in their pajamas, some in college T-shirts where their parents undoubtedly were educated, and none of them appearing at all to be thinking of going to church. Maybe they went last night. Maybe it was just too early and they would go later. Maybe. I hope so. Yet it seemed like this day was like any other day, for them. No, no, it was different. This was their “family day.” This is a day to lounge in Dunkin Donuts and then go home to watch television or perhaps spend more time surfing the web or updating their Facebook page—at age seven. I have nothing against iPads and computers or Facebook or emails. I am writing on a Mac right now. But the digital age has also produced unintended consequences that touch the very lives of our children. And I saw, in that moment (only moments ago, now, as I write) a new generation of children in a new, gruesome kind of servitude. My heart was broken. I thought to myself, “These children are no different from the children who were in the grungy captivity of an indifferent Industrial Age—they, too, are being maltreated, cast-off, and denied the simplicity and “innocence” of childhood. Most sadly, they are being deprived of a life with God. They’re being denied learning the Sunday school songs that we learned as children. They are being denied the teaching of the Word of God. They will not stand as a class in front of the congregation to recite John 3:16 or hear a kind lady whisper in their ears, “Jesus loves you.” For children to miss the Lord, when steeples of churches rise all over the landscape of our nation, is to be as shackled and abused as the smudged faces that stare back at you in the drawings from a Dickens book. These children are mostly affluent, yet they are in the worst sort of poverty, the poverty of the soul. Secularism, eating away at the last residue of faith passed down to their parents from their parents, is stripping them of the abundant life that Jesus promise; and, if left undone, will send them into an eternity of Hell. Someone in my mind says, “But there can be no law against this. This is not like Dickens’ days at all! You cannot equate suburban children living in affluence with the underprivileged children of the Industrial Age. Their parents have made the choices. The parents are rearing them in a different way from the way you would rear your children. They are free.” No, I say. They are not free. Their parents are mistreating them and leading them into a world without God and that is an abuse that will have consequences in our lives, in our nation, in our world, and eternity which we cannot even imagine. Yes, they are free to rear them the way they think best. Of course. But must I not share that there is a better way? It is better to be true than to be quiet. This is what made Dickens “great,” as Chesterton put it. The society is misusing these little ones. The children are being marketed and manipulated by a sinister, new age—a Digital Age, if you will — that has enticed their parents into thinking that their products will bring something good, when in fact, it is putting their souls in shackles and leaving their minds impoverished—not for information, but for wholesome truth and happy moments that only the Bible and the community called the Church can give. I looked at the children at the tables, quite obviously about to spend yet another day without any thought of God, without any thought of the goodness and glory and majesty of the Triune God, which provides the image of God to our humanity, and I felt sick to my stomach. Have you ever been to the photographic show displaying the monochrome pictures from the days when factories and mills—and a society that allowed it—abused poor children? My family and I recently saw such a show at the North Carolina Museum of History. In our own state, far away from the drudgery of child labor in the London factories and mills, we had our own textile mills that took advantage of children to increase the yield of their fabric. The photographs revealed, in unforgettably sad fact, the truth of our own call culpability in the inhuman child trade of another period. Yet, before my eyes, this morning, I saw these affluent, suburban children in the same way. For a moment the room—this Dunkin’ Donuts shop—seemed like one of those faraway textile mills with the unhappy children looking out, not from giant spinning wheels, or from backbreaking work on the floor of a grimy factory, but just looking blank—if not every bit as gloomy.

Dickens was a great man, Chesterton told us, because he saw humanity in poverty. He did not pity the poor as a Lord of a manor pities the wretched souls who pay him rent for the dilapidated housing he offers them. Dickens pleaded for them as real people who deserved justice. He wanted more for them. We, too, must not simply look out upon the world of unbelievers with pity that they don’t have what we have, but we must look out with the compassion of Jesus as he looked out upon the multitudes in Matthew chapter 9. These were sheep, our Lord called them, and they was scattered—cast down—and without any shepherd. He called for us to pray for shepherds to go into God’s harvest. Did Jesus look with only pity at the multitudes, or was his deep emotion a tributary of His divine love? He looked at a harvest that he called “plentiful.” He saw great and glorious things for otherwise diminished people. He did not pity. He had compassion. There is a difference. He advocated. And shall we not respond?

When I was a boy each summer churches what whole Vacation Bible School parades. We also held Sunday School outreach events for children. Perhaps they still do that in some communities in America. I do not know. In all of my years of ministry, I do not believe that we have ever held at Vacation Bible School parade in any of the affluent suburban communities that I have served. Maybe it’s time that we bring a parade back. Maybe it’s time that we go out into the highways and byways of suburbia, to look upon the impoverished children caught in the inhumane cogs and spinning wheels of this age, burying them under the insufferable weight of their parents indulgence, and bring them the Word, and show them the joy, and draw them with the honey of goodness, that would bring them back into Sunday school and church. If we believe that we have something good for these children, and we do, then let us reach them or let us die trying.

I left the Dunkin’ Donuts, returned to my car, turned to my son, and told him, “go and teach the little boys under your care today. Teach them well. Show them Jesus. He is the only way to unloose them from the bondage of the digital shackles that have been placed upon them even this week.”

Oh, that there would be great men and women in our age to see the nobility of the child and the disgrace of the shackles in this sinister and uncaring age. Dickens’ work resulted in a public awareness of the plight of thousands of children. Laws were reformed. Children were set free. Believe that it is time for our pastors to cry aloud and spare not, to be “great men” and raise the awareness of our children living without God. Such spiritual activism will also produce reform—not in the laws of the land—but in the law of love and the beauty of a child set free.

Chesterton, G. K., and Readers Club New York. Charles Dickens, the Last of the Great Men. New York,: The Press of the Readers Club, 1942.

Postman, Neil. The Disappearance of Childhood. New York: Delacorte Press, 1982.

[1] G. K. Chesterton and Readers Club New York., Charles Dickens, the Last of the Great Men (New York,: The Press of the Readers Club, 1942).

[2] “For you always have the poor with you, and whenever you want, you can do good for them. But you will not always have me” (Mark 14:7 English Standard Version [ESV]).

[3] Neil Postman, The Disappearance of Childhood (New York: Delacorte Press, 1982).